Contents

1) Prelude

2) The Long Climb Up Mt FACEM

3) The Exit Exam (Fellowship OSCEs)

4) What was the Emergency Medicine Training program like?

5) Special Thanks

1) Prelude

Specialist training is a bit different in Australia compared to many other

countries - becoming a specialist does not involve universities or masters

programs. So unlike universities with an impetus to have high pass rates and

good reviews, the opposite is true. Becoming a specialist is like joining a

club of enthusiasts who are interested in a particular field. They dont do

this for the money - it's a passion for them, especially the examiners and

senior college members. The ones holding the keys to the gates are taking a pay

cut to be involved in the examination process - setting the standard is a

responsibility they take very seriously. It's a lifestyle. A vocation. The

training program ultimately answers four questions:

1) Are you a safe doctor that

meets the current standard of care? (medical expertise)

2) Will I be happy for you to look after my mother? (empathy)

3) Can you lead a department? (leadership, prioritisation)

4) Will you make the department/world a better place? (health advocacy / systems

/ processes)

The above

takes time. The ED Training program can technically be passed in 5 years. I

took 9. The college requires you to pass within 12 years. It sounds like alot,

but trust me the years will fly, and many people take time off for other things

(parenting etc).

Above all

else, ED Training is an apprenticeship with exams. You will work as a

registrar with consultant oversight, and be gradually given more

responsibilities and key decision making roles. The ED tier-list is roughly as

follows:

Intern / PGY 1- All

patients discussed and seen in person by a senior.

PGY 2 - All patients discussed with a senior.

PGY 3 - Most straightforward bog standard presentations managed

independantly.

Junior Registrar - Straightforward presentations managed independantly.

Others discussed.

Senior Registrar - Complex presentations managed independantly. Can run

department when required; especially at night, but requires consultant advice

and support occasionally.

Principal Registrar - Able to run department at the level of a

consultant, with other consultants available for mentoring.

Fellow – You have joined the college, but yet to sign your fat juicy

consultant contract.

Consultant - The buck stops with you. Google and Bing maybe? I heard

AskJeeves is no longer used. I might just crack open the textbook. Or perhaps use that jedi-mindforce gestalt from years of experience.

There are

a total of 4 exams. Keep in mind the doctors sitting these exams have been

working for many years and have a keen interest in emergency medicine. They

were all > 97th centile in highschool/college. Then after finishing

medschool and proving themselves on the ED floor, they were all deemed fit for

entry into the training program by two senior emergency consultants. Despite

this, roughly one third will fail every exam. When i sat the Fellowship

Writtens, the pass rate was only 59%. Fail 3x (primary) or 4x (fellowship) and

it's THE END (you will be removed from the training program). The stakes are

very high. I failed OSCEs on my first attempt - and the preparation for round 2

nearly broke me.

The Primary Writtens: It's

like med-school, but with a much lower pass rate and a focus on ED relevant

anatomy, physiology, pharmacology and pathology. Also, unlike med-school, you

will be working full time while preparing for this. Enjoy =)

The Primary Vivas: A bit

more clinical. Can you talk about the above topics coherently?

The Fellowship Writtens:

It gets real. Real life medicine. Application of knowledge.

The Fellowship OSCE: Dials

realism up a notch. Actual on the floor performance is assessed. Paid actors

will be in tears if needed. Challenging complex presentations. Boring mundane

things you are expected to do very well. Are you performing at the level of a

consultant? There are no tricks. They are not trying to fail you. You need to

be quick, adapt, and apply consultant level knowledge/heuristics on the fly. 7

minutes per station. 12 stations. I was almost in tears when it was over. The

preparation for this exam almost broke me. The sound of the end-station bell

triggers PTSD in many consultants for a reason. This exam is unlike any other.

It is ultimately a consultant level benchmarking exam.

A

particularly time consuming part of the training program is the research

requirement. Regulation 4.10 it's called. You can either do a statistics

course from a recognized university, or publish as first author in a reputable

journal. I was very fortunate to have contacts from my Monash days and

published an article in the Annals of Emergency Medicine. Research is hard. I

do not recommend this route - the biostatistics course is probably much easier.

On the plus side I now know how to use basic statistical analysis tools. In

addition to the above, there are other requirements at various stages of

training just to spice things up a bit.

2) The long climb up Mt FACEM.

2003 - Finished Highschool

2005 - International Baccalaureate Diploma

2007 - 2011 Monash MBBS (Selection ATAR / Centile > 97%)

2012 – Internship

2013 - Hospital Medical Officer

2014 - Start of Emergency Medicine Training

2015 - Year off as unaccredited Intensive Care Registrar

2016 - Decided ED training is more exciting. So back to ED Training.

2017 - ACEM Primary Writtens and Primary VIVAs

2018 - 6 months in a Rural ED (3 hours from melbourne)

2019 - Research Requirement. Published paper in a high impact journal.

2020 - Advanced Training time. Certificate of Clinician Performed Ultrasound (CCPU)

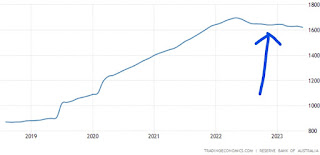

2021 - ACEM Fellowship Written Exam (59% pass rate)

2022 - Start working true in-charge shifts; running the floor/department.

2023 - ACEM Fellowship Clinical Exam (67% pass rate)

I graduated third in my highschool. Being thrown into the Monash MBBS cohort was quite a departure from what I was used to. I have never felt more average. Every one in the room was from the top of their class.

In medicine, you will be exposed to various departments as a junior medical officer. Time seemed to pass quickly in Emergency, so I thought - why not. I joined the college of emergency medicine in 2014 and spent a year at Clayton hospital (Tertiary referral) and Dandenong hospital (Urban district). I was probably a bit too green for the job at that point. Reviews were less than stellar. I was considering switching course.

Took a year off to try my hand at Intensive Care - I was only four years out, and probably a bit too green for that job as well, but it was a very good learning experience. This was when I started to really develop key procedural skills and become comfortable looking after sick patients.

2016 was the year ED training really began in ernest, and my first taste of failure. I failed the Primary Viva that year. I was quite unprepared. You need about 500-1000 hours of preparation for both the primaries and fellowship writtens. But at least you could study/prepare for it. The OSCEs are a totally different ballgame. Studying for the OSCE is moot.

3) Exit

Exam - The Fellowship OSCE

It is a

true exit exam, unlike other colleges whereby you sit for exams in the third

year, and 'do your time' so to speak apprenticing on the job for the next three

years. The ACEM Fellowship OSCE is a consultant level benchmarking exam,

whereby you are tested against real emergency consultants as well as the rest

of your cohort. The test is thorougly curated. A bunch of blinded consultants

will sit the exam and a benchmark score will be created for each station. Could

you perform at the level of a junior consultant? That is what is assessed.

Roughly 2/3rd of those sitting will pass, but this includes those sitting for

the 2nd, 3rd and 4th (final) time. Realistically (and anecdotally from my study

groups), roughly half of those sitting for the first time will pass.

Everyone

sitting this exam has had 4-11 years of ED experience at the registrar level,

and had passed both the primaries and fellowship writtens. Knowledge is a given

- this is not a test of knowledge. In my first attempt I made this mistake. I

studied for this exam - I went through the entirety of the syllabus and my exam

resources. I failed.

The

preparation for my second attempt took a full year. It required a complete

change in my thinking, and ironed out alot of the idiosyncrasies and bad habits

you tend to accumulate over the years - and made me a much better doctor as a

result.

In my

time of need, the esteemed members of the college came to my aid, and polished

my practice of medicine to the level of a FACEM. I did not pay them anything

for this - their only request is that I pay it forward - which I will. FACEMs

with decades of experience sat down with me 1:1 and went through OSCE

scenarios - and helped polish my responses. This is the real GOLD of the FACEM

training program. It is not in any official document or rulebook. It’s the intangible

benefit of mentoring and support from members of the club.

The OSCE

process was life and practice changing. It really took me up a notch in the way

I interact and conduct myself in real life and on the floor. This is what makes

the ACEM Fellowship quite special. This is not an exam that could be studied

for. There is no textbook. Knowledge is a given. It is about you, as a

person, dealing with real life situations – all stations are based on real

life. You cannot fake it. You cannot script your answers. It is about how you

process information. Synthesis. Third order thinking, as my mentor puts it. You

then need to be able to communicate that information appropriately to other

consultants, nursing staff, students, and the average layperson. Demonstrating medical

knowledge is the bare minimum required, and you will still fail if you do not

address the human factors, health advocacy, leadership, prioritization and

other domains assessed.

After

many years of real world clinical practice, the OSCE will make sense. If you

have qualified to sit the OSCE, I have some tips below.

How I

got through the OSCE.

The advice below is my experience from having failed the

OSCE once.

Do not study for the OSCE. *practice* for the OSCE.

Leading

up to the OSCE, you should be practicing every single day you are not working

on the floor, and on every day you are working on the floor. This is

harder than it seems because of the shift work, and everyone having different

schedules. Also remember that every single real-life interaction at work is

effectively an OSCE – think about how the domains apply to your everyday

practice and polish your performance to give off that consultant vibe.

In the months prior to the OSCEs, I was eventually having

sessions 4-5 times per week, in addition to working full time doing shift work.

This is a life-stopping soul crushing amount of work. Keep in mind a lot of

time goes into logistics, travel and planning as well. You will need an OSCE

buddy as many OSCE scenarios utilize a confederate. I had Kevin, who joined

many of the sessions, and we grew together through the OSCE learning process.

He passed too.

Practically,

what you need is a forward rolling availability calendar, then every

time you have a session with someone – make sure to book in the next session!.

That way you can slowly build up a schedule and fill up all slots.

For

example, this was my actual real life schedule in the 4 weeks leading up to the

exam. This went on for two months and damn well near broke me.

Monday Ruth

9am, Ben 12pm

Tuesday Garry 7pm

Wednesday Work 2.30pm to midnight.

Thursday Mohan 10am, Work

2.30pm to midnight.

Friday Cabrini Trial Exam

Saturday Work 2.30pm to

midnight.

Sunday Work 2.30pm to

midnight.

Monday Darsim

2pm, Mohan 10pm

Tuesday Mohan 10am, Darsim

3pm, Garry 7pm

Wednesday Monash Trial OSCE

morning. Then Work PM Shift 2.30pm to midnight.

Thursday Mohan 1pm. Work Night

Shift 11pm to 8.30am.

Friday Imran 9am. Work

Night Shift 11pm to 8.30am.

Saturday Mohan 9pm. Work Night

Shift 11pm to 8.30am.

Sunday Mohan 9pm.

Monday Garry

7pm, Mohan 9pm

Tuesday Jo Dalgleish 1pm,

Work PM Shift 2.30pm to midnight

Wednesday SIM TEACHING SESSION

morning, then Work PM Shift 2.30pm to midnight.

Thursday Abrar 10am, Mohan 12pm,

Work PM Shift 2.30pm to midnight

Friday Jo Dalgleish 10am,

Darsim 12pm, Work PM Shift 2.30pm to midnight

Saturday Mohan 10pm

Sunday Mohan 10pm

Monday Start

Planned Annual Leave. Mohan 9pm

Tuesday Jo Dalgleish 12pm,

Garry 7pm

Wednesday Frankston OSCE trial,

Ruth Hew 3pm

Thursday ECG/VBG/Xray refresher

Friday Toxicology

refresher

Saturday Shayaman session.

Sunday Frankston OSCE trial

2 by Mohan and Abrar 1:1 face to face.

Correct Circadian Rhythm

Align circadian rhythm

and set up a routine whereby I would have a cup of chamomile tea, and sleep as

much as possible every night. It will be very difficult to sleep the night

before the OSCE – this is quite possibly the single most important thing in

preparation that few people realize. Nobody sleeps well before the OSCE. If you

are interstate, fly in two days earlier and get used to the hotel/bed. Hotel

too noisy? Switch hotels. I took annual leave before the exams so I could set

up my circadian routine.

Know the uncommon but important to know stuff

An

exciting aspect of emergency is that we deal with rare presentations, and are

expected to know how to deal with them reasonably well. Think

methaemoglobinaemia from nangs/poppers, variants of ACLS (pregnancy,

hypothermia, TCA OD), toxinology (snake bites), thyroid storm, the RBBB STEMI,

and all the random critical things you may (or may not) have seen in your ~10

years of being a doctor. And know how to do them well.

This is where your OSCE practice comes in. You would have at

least been in a OSCE practice scenario involving a rare but not to miss

condition that you may not have encountered in real life. I failed the

toxicology station in my first attempt because I wasn’t polished enough about organophosphate

poisoning. I knew the basics, but knowledge alone will not guarantee a pass.

There Are No Tricks

The

examiners are not trying to fail you. You just need to demonstrate what you

already do every day at work on the floor. For example, the ECG station in my

first attempt was that of a young 9yo girl with chest pain. I was interacting

with an intern who has come to me with that ECG. My opening words were “Well

they are obviously juvenile T waves and nothing to worry about”. But as the

intern discussed the case, she started asking about other things, and I

eventually asked her to get a paediatric cardiology opinion – that’s a fail.

Stand your ground. Have faith. Use the force. My second time around the ECG

station was a boring bog standard pericarditis, and a HMO who is worried about

ischaemia. Nailed it. How you describe your reasoning in a way that is

understandable to your target audience is important. If it quacks like a duck,

it’s a duck. You don’t need to consult a professor of Ornithology to confirm

your convictions is not a chicken. You would however describe a duck

differently to a kindergardener and a university student of biology, which

brings me to my next point:

The Special Sauce.

Always

ask yourself – why is this in a consultant level exam? The exam board is

transparent in that the domains are always given, so you know what you are

being examined on. Teaching? Leadership? Medical expertise? If it says 60%

teaching for a boring bronchiolitis baby case, then be sure to place emphasis

on your delivery of content attenuated to the level of the person you are

teaching – blurting out the entire RCH guideline on bronchiolitis to a

doe-in-headlights intern will be a clear fail. The station tests if you have

tought and supervised interns before. Medical knowledge is a given at this

point. If the case is very straight forward, there is always some special sauce

somewhere that will give you a chance to demonstrate your consultant level

responses.

All answers need to be clinically relevant and demonstrate

breadth of knowledge that is prioritized due to the fast paced nature of

emergency medicine. This is not a physicians exam. There are no long cases. For

example, in a bog standard presentation of an elderly person with abdominal pain,

mentioning porphorya, retroperitoneal fibrosis, pancreatitis from scorpion

venom, and epiploic appendagitis will not win you any points. ED exists

ultimately to exclude red flags and make appropriate referrals in these

situations. Think broad. Take one step back. Vascular catastrophe (TAD / AAA),

Endocrine (DKA), Visceral (PUD / Pancreatitis), Surgical (SBO/LBO,

diverticulitis, appendicitis, hernias), Cardiac (atypical MI). Focusing on just

surgical causes for example will be a fail for that question. What would you do

in real life? Do that. You cannot fake it. It is about you, as a clinician.

The Feels.

It is

easier to do something than to do nothing. Any registrar can correctly treat an

infective exacerbation of COPD, but a consultant knows when to stop and switch

to comfort focused care (palliation), and how to break the news to the patient

and family. You would have likely been a part of these types of discussions in

real life at some point prior to the OSCE, but you will need to polish it

to sound like a consultant and develop rapport and trust with

patients/families. Sure you can make the correct decision to palliate, but the

situation may involve you breaking the news to a relative. The paid actor will

be in tears in the real exam.

4) What was it like being an Emergency Medicine Trainee?

it is a full time 86hr/fortnight job

1/3rd of all shifts are night shifts (11pm to 8.30am).

1/3rd are morning (8am to 5pm), 1/3rd are afternoon (2.30pm to midnight)

It's a 5-12 year commitment depending on how fast you progress.

You will do a rural/remote term (6 months) in a far out place. The META of a rural ED is quite different and is an invaluable experience to have.

You will do a minimum of 6 months of combined ICU/Anaesthethics (I did 18 months total as an ICU registrar, and 6 months of Anaesthethics)

College fees are about AUD $2k per year. Each exam is about AUD $3k.

Mentoring at least 1-2x a month (workplace assessments)

At least 48 months of working in ED.

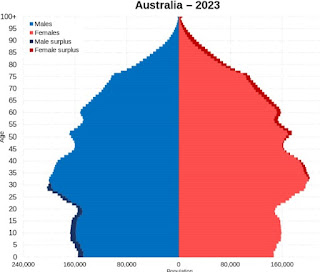

See at least 400 sick kids. (I saw closer to 1200 by the time I reached fellowship)

Some non-ED time doing non-ED things. (I did ultrasound)

10000 hours?

It is said you need 10000 hours to become good at something. Well, working 47 weeks a year (5 weeks annual leave) for 9 years = 18189 hours. Each exam took 300-500 hours of preparation, or about 1500 hours total. Then add a few hundred hours for research, courses, presentations and workplace based assessments. It took about 20,000 hours for me to reach this point. Im a slow learner.

Why did I do it?

Because ultimately it's fun. I dont find the job onerous and look forward to going to work despite the high stress nature of the job. Time passes quickly and I find myself staying back to get stuff done instead of dreading every minute at work looking forward to go home. I've called in sick once in the last three years and that was because of PCR confirmed COVID and I was kinda forced to do so. I have *never* called in sick on a night shift.

If you find yourself dreading to go to work, this is not for you.

5) Special Thanks

The Family

Peggy - My wife. The rock that keeps me grounded through very tough times. She shared the stress of the exams and was there for me in times of need. This exam damn well near broke me. I could not have done it without you.

Mum and Dad – for the encouragement and support over the years.

The Senior Emergency Consultants

Mohan Kamalanathan - The Mentor. Who had seen me through the past 7 years of training and spent so, so much time with me to polish my performance, both in exams and in real life. A very senior examiner. Sometimes when im stuck i'll go - hmm, what would Mohan do? A true mentor. Yoda, he is.

Abrar Waliuddin - The OSCE nerd. Tons of simulated OSCE practice, including the two mock OSCEs and many many in person sessions. This guy went out of his way to design OSCEs and run the fellowship training program in Frankston hospital. He wrote the Frankston OSCE guidebook.

Garry Wilkes - The Examiner of Examiners. How to deal with very difficult leadership and empathy scenarios. He trains the new first time examiners. His advice on dealing with difficult scenarios is practice changing. Not just in exams but in real life.

Jo Dalgleish - The Lead Examiner. The literal chair of the ACEM examinations committee. For helping me brush up my performance and thought processes for the OSCE. How to think like a FACEM.

Imran Chanth Basha - The Contact. I've only known Imran for a year, but he got me in touch with Jo and Ruth. Absolutely priceless. Legend.

Shayaman Menon - The Director of Directors. An Emergency Physician who has risen to become the overarching Director of Medical Services. Also an examiner. Had a few sessions with useful feedback and confidence building.

Ruth Hew - The Oracle. Tells you exactly what *you* need to hear. Her feedback was invaluable. A very, very, senior examiner (Turns out she was Shayaman’s mentor back in the day). Lives in a house full of character. Gives you baked goods. Motherly vibes. Here, have a cookie.

Darsim Haji - The POCUS Guru. An examiner, who is very adept in ultrasound. Helpful sessions and feedback on the floor. Well respected examiner and mentor from my ultrasound rotation days, who spent some time polishing OSCEs with me.

Jon Dowling - The Trainee Whisperer. The nudge in the right direction to not sit 6 months later and to properly prepare was gold. Looking back there is no way I would have passed if I had just gone straight for the next exam sitting. Jon is very good at clinical processess and leadership - when encountering a leadership situation I find myself asking 'what would Jon do?'

Gabriel Blecher - The Director. He is the current director of my department. I was feeling quite low after failing my first attempt. His positive feedback was invaluable in rebuilding my confidence. Sometimes you forget about the things that do go well and dwell on things that dont.

Diana Egerton-Warburton - The Researcher. Last but not least, the Professor who helped me get published for the fellowship research requirement. She is the most accomplished researcher I know in person. Holds an Order of Australia (OAM).

What Happens Next?

You look in the mirror, notice some grey hairs, and come to the stark realization that you are now the pointy haired boss. You have a director and executives above you, but you are running the floor. The juniors have to (at least pretend to) like you for good term assessments and feedback. You have earnt the title of Fellow of The Australasian College of Emergency Medicine, and can get your fancy FACEM self-inking stamp.

Welcome to middle management.